How do you Compare Players across Eras?

In my real job, I occasionally review scholarly papers for academic journals. Last week, the Journal of Quite Interesting Value Theory sent me a strange piece to look over, one that didn’t really fit any of the norms of professional philosophy. The writer – peer reviews are anonymous, so I don’t know who it was – was arguing, it seemed, for the value of human over natural beauty. The main argument appeared to be that a particular person was more beautiful than even paradigm cases of great natural beauty, and in several ways.

Anyway, I told the journal to reject it. Even ignoring the curious style, with its archaic language and the complete absence of footnotes or a literature review, the basic premise was misguided. How can you compare a person to a summer’s day? What did it really mean, when you got right down to it, to say a person was “more lovely and more temperate”? Wasn’t it egregious anthropomorphising to claim that “sometimes too hot the eye of heaven shines”? As I pointed out, I think incontrovertibly, heaven doesn’t have an eye.

Finally, with a somewhat daring flourish in which I continue to take a certain amount of quiet pride, I said the piece was “comparing apples with oranges”.

Which, of course, is what some people think I did in my piece on Virat Kohli and Sachin Tendulkar. I’m not interested in defending or renouncing that piece. But I am interested in exploring one objection people made to it, namely that the whole project of comparing the two is invalid because they played in different eras.

There certainly appears to be something to this. For example, in 35 Tests, Archie MacLaren scored 1931 runs at an average of 33.87, with five hundreds and eight fifties. In 40 Tests, Yuvraj Singh has scored 1900 runs at 33.92, with three hundreds and 11 fifties. The numbers are similar, but it would be absurd to use them to say that the two players are about as good as each other. On the one hand, MacLaren played on worse wickets and with much worse equipment. On the other, Yuvraj played in an era with much better standards of fielding, greater focus on tactics and analysis, and higher standards of fitness and training, which one would expect to increase the impact of the average quality of the bowling he faced. How on earth can we make any kind of meaningful comparison between the two?

One solution might be to compare within eras, and then use differences with peers to make cross-era comparisons. So, for example, you see how much more Don Bradman averaged than everyone else in his era, and compare this with how much someone would need to average now to have the same difference, and voila, you have an apparently knock-down argument that demonstrates Bradman was better than any other batsman who has ever played.

But there are problems with this too. For example, Stephen Jay Gould has argued (in the context of baseball) that the reason Bradman-type careers don’t happen nowadays is not because there’s no one with Bradman-type talent but because the average level of cricketers around the potential Bradmans keeps going up. Whether or not this hypothesis holds, the underlying point is that it shows another issue for cross-era comparisons, namely that if you’re going to compare by using distance from the mean, you have to be sure that the level of the mean is constant over time. Further, in a sport like cricket, the average level has an effect on the performance of a given cricketer, so if bowlers are on average better than they were in the 1930s, this will have an effect on the performance of batsmen.

There’s a much longer debate to be had, of course, and one can achieve a lot more with numbers than I can even understand (Anantha Narayanan regularly does interesting pieces of this kind on this site). But still, these sorts of problems can motivate the view I mentioned, that we should simply stop making comparisons across eras. This is legitimate to believe, and you can certainly defend that view. But it’s worth pointing out one of its consequences: it means you can’t say that Don Bradman was a better batsman than Chris Martin. That’s simply entailed by saying you can’t make comparative judgements across eras – it doesn’t only mean that you can’t make difficult comparisons, it also means you can’t make the ones that seem obvious.

“Better than”, however, is only one type of comparative judgement, and when it comes to cricket, by far the least interesting. Let’s say you manage to somehow establish that MacLaren was better than Yuvraj. So what? What have you learned beyond that?

The more interesting sort of comparison, at least to me, is a kind of “reminds me of” relation. This is comparison as simile or metaphor. As Aristotle pointed out a while ago, we learn from a good metaphor, because when you say X is like Y, you learn something new about both X and Y. By regarding an unseen similarity, you learn a new feature of both X and Y.

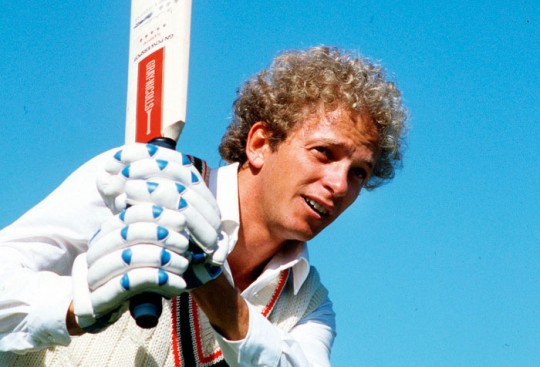

Just off the top of my head, for example, Ajinkya Rahane reminds me of David Gower. I make no great claims for the educational value of this simile, but I think even at first glance it’s more interesting than “Rahane is better than Gower”. There are some obvious similarities I see between them, namely the elegance of their strokeplay, the almost peaceful way in which they strike the ball (neither of them hits it, even when it goes for six). They bat like Nehru under the influence of Gandhi’s non-violence.

And there’s something a little less obvious, perhaps. No one has ever accused Rahane of lazy elegance. Grit, a capacity for hard work, determination, a certain quiet, undemonstrative toughness – it’s obvious Rahane has these qualities. The comparison between him and Gower may lead us to wonder, then, whether people sell Gower short when they talk about his foppishness; whether, in fact, Gower was also, in a certain sense, steely like Rahane seems to be.

What you think about the details of the comparison isn’t important. My point isn’t that I’m right about Gower and Rahane. Rather, it’s that when we compare across eras, it may be more fruitful to talk in open-ended ways, to ask questions that invite qualitative discussion, to use simile and metaphor, rather than to ask the tired old question of whether one player is better than another.