Benson and Hedges World Championship 1985 final: Rekindling fond memories of India beating Pakistan

India beat Pakistan in the final of the Benson and Hedges World Championship of Cricket to complete a near perfect tournament triumph.

An unlikely final

Not every fan who had pre-booked his seat for the Benson and Hedges World Championship final was amused.

An India-Pakistan clash generally over-stimulates the imagination of the cricketing community around the world, resulting in a tumult of emotional cocktail always intoxicating and often provocative. However, not everyone in Australia expected the tournament title round to boil down to a subcontinental showdown.

“Benson and Hedges Final: Bus Drivers versus Tram Conductors,” screamed a banner at the Melbourne Cricket Ground (MCG) on that epochal day.

Yes, even as late as 1985 the patronising attitude towards the subcontinental sides was blatant. For almost a decade, West Indies had ruled the world single-handedly, and their supremacy had been accepted with the barrage of bouncers one struggled to evade. The team from the Caribbean had carved an unprecedented dimension in a game largely seen as an extension of the Ashes. But, no one had really expected India and Pakistan to run away from the rest during the home stretch of a tournament of this scale.

Why, Australia themselves had travelled to India in late 1984 and had routed the hosts 3-0 in a One Day International (ODI) series marred by rain and mismanagement. The 1983 World Cup triumph now seemed far away. Since then West Indies had come down to India and trounced the hosts 3-0 in the Tests and 5-0 in the ODIs. England had done likewise, although with significantly less degree of brutality. And,in between the two series, the Australians had trampled on their pride and prestige.

In the aftermath of a litany of losses, even the Indian public did not give them much of a chance. Those were days when the World Cup win had just about sunk in, and treated as a freak event. Indian fans were not yet accustomed to wins and did not yet demand World Championships as their justified birth-rights as they would do two decades down the line.

Pakistan too had not really set the cricket grounds on fire in the recent past. Since the 1983 World Cup they had lost Test series in both Australia and New Zealand. They had managed only one win in the three-nation Benson Hedges World Series involving West Indies and Australia in the last southern summer. Two months before the tournament they had lost 3-0 in a bilateral ODI series in New Zealand.

The progress of these two sides to the final was viewed as an anti-climax, the sure-shot formula for an insipid end. Except for reactions of surprise and excitement in the two throbbing Diasporas, interest remained low.

However, there could not have been two more deserving finalists.

The unchallenged routes

Sunil Gavaskar’s men had been ruthlessly efficient, most unlike an Indian outfit. They had won every match leading up to the finals and had done so convincingly. The bowling, the eternal weak link in their setup, had systematically vanquished opposition after opposition. Their batting consisted of amazing pedigree and depth. Their fielding reached standards of few Indian teams before or since.

In the group stage, none of the teams had managed to reach 200 against a combination of talent and efficiency stretching across pace and spin. Pakistan had been overcome by six wickets, Australia by eight wickets, England by 86 runs.

In the semi-final, New Zealand had inched their score past the 200 barrier to total 206. For a while, the Indians seemed to be in trouble. But, a magnificent association of class and thrill between Dilip Vengsarkar and Kapil Dev had settled the issue with seven wickets and 39 balls to spare.

Javed Miandad led Pakistan had lost only one match on their way to the final — that to India. Their victories had been convincing as well, overcoming Australia by 62 runs, England by 67 and upsetting the mighty West Indies by seven wickets in the semi-finals.

There was no doubt about it. The best two sides had made it to the title round.

The India-Pakistan ODI encounters had yet to take on the stature of the titanic tussles witnessed from the mid-eighties, conflicts that brought the two neighbouring countries to absolute stand-still, with national well-being depending heavily on the outcomes. However, given the complex historical threads binding the two sides, there was plenty of interest nearer home.

Just as the two teams took the field, a report described the sides as ten Hindus and one Muslim (Mohammad Azharuddin) against ten Muslims and one Hindu (Anil Dalpat). The bordering countries were expected to be anything but neighbourly in the match.

The early inroads

Roger Binny, who had played such a vital role in the exceptional bowling performances, was down with a virus and had to miss the match. Chetan Sharma came into the side, the only change effected by India in the entire tournament.

Miandad won the spin of the coin and elected to bat, perhaps based on the sound principles of batting in the day-light and the possibility of the wicket taking more spin later on. And as usual Kapil produced another fantastic spell at the beginning.

When we look back at the tournament, our mental picture is generally of the all-round excellence of Ravi Shastri winning the Champion of Champions Award, and thereby the swanky new Audi. Of course, no one can deny his miserly spells throughout the tournament and the solidity he provided at the top of the order. However, if one looks at Kapil’s nine wickets at 14.90 apiece at an economy rate of 2.97, one realises how crucial his role was in providing the initial impetus for India in every innings.

He reached his peak performance in the final, as he swung the ball around at will. The experienced opening pair of Mohsin Khan and Mudassar Nazar found him incredibly difficult to score off. At the other end, Kapil’s protege Chetan ran in with plenty of zest.

Yet, Kapil’s first wicket was somewhat fortuitous. Mohsin Khan played casually at a ball at waist level going down the leg side, and hit it straight to Azharuddin at square leg. It was 17 for one.

Rameez Raja, who had been one of the architects of the win against West Indies, came in and struggled against the Haryana duo. He tapped one to the side and set off for a quick single. The slight, sprightly and agile Laxman Sivaramakrishnan sprinted in from cover, and crashed into the huge frame of umpire Raymond Isherwood. It was an early scare for the Indians as this splendidly talented leg-spinner clutched his jaw in pain. But, thankfully the collision did not prove critical.

The long spell along the corridor of uncertainty now bore fruit. Kapil finally strayed in line and sent down a near wide. And Mudassar, whose patience knew no bounds and had once seen him score the slowest recorded hundred in Test cricket, now flashed at the ball. Behind the stumps the electric form of Sadanand Viswanath dived to take the edge in front of the first slip. It was 29 for two.

In walked Qasim Umar, the stylish touch player with enigmatic African roots, another hero of the game against West Indies. And Kapil sent down a blistering in-swinging yorker. It was a cruel ball to get first up and while still completing his forward stroke, Umar heard the rattle. The score read 29 for three.

It was the captain who now walked in. Street-smart, classy Miandad. Kapil was on a hat-trick. He ran in, with his measured strides and that impeccable action. The ball was vicious, spitting up from short of good length, and would have done in any lesser batsman. Miandad played it from the front of his face, bat loosely held in the left hand, the right off the handle. The ball dropped in front of his feet, inches from the crease. Miandad’s front-foot soon moved in line with the ball, the bat came down straight and the ball sped through the covers for four. A contest to cherish for ages.

From the other end, charged in Chetan. And Rameez flicked him with splendid timing. But the ball was in the air, dipping, and at square leg, just behind umpire Tony Crafter, Krishnamachari Srikkanth scooped it up as it was dying on him. A slight nod from Crafter guaranteed that the catch was clean. Pakistan were 33 for four in the 12th over.

The great Imran Khan walked in and almost immediately met with a scare. Chetan’s bouncer reached him a bit too quickly, got past the attempted hook and took the glove on the way to Viswanath. The Indians were certain, we definitely are after watching the replay numerous times. However, Isherwood remained unmoved. Chetan could not believe it. And it was almost as difficult for Imran to believe his luck.

The experienced pair was now left with the task of rebuilding. The bowling remained steadfastly accurate, acceleration remained difficult. There were rare moments when the shackles were temporarily broken. Imran stepped out to hit the medium pace of Madan Lal down the ground, and then lofted Shastri inside out over cover. But, the overs started to run out with Shastri and Sivaramakrishnan bowling in tandem. Mohinder Amarnath, as he had done throughout the series, bowled wicket to wicket, a most difficult customer to get away.

Sivaramakrishnan’s magic

The score did cross hundred with only four down when captain Gavaskar exemplified the brilliance the Indians had shown on the ground all through the championship.

It was also the result of a scintillating spell of leg-spin by young Sivaramakrishnan. Even these two men of immense experience and quality against the turning ball were tied down as he sent in his incredible mix of leg-spin and googlies. Desperate for quick runs, Imran dabbed the ball to point and set off for a single. A shocked Miandad sent him back. But, Gavaskar rushed in, picked up and sent in the return in one fluid motion. It crashed into the stumps at the striker’s end. Imran walked back for 35. The veteran pair had put on 68. It was 101 for five.

There was more Sivaramakrishnan magic on the way.

Young Saleem Malik came in with the intention to push the score along. A drive off the Indian leg-spinner went high to cover, but Shastri was slow to react. Soon, however, the spinner flighted it again, Malik lofted, and Chetan ran in from long off to hold a well-judged catch.

The batsmen had crossed. The next ball was a tempting leg-break, tossed up on the leg stump. Even a batsman of Miandad’s calibre was drawn down the wicket into the drive. The ball dipped at his feet and turned like a top, beating his bat, going past the off-stump, and the lightning gloves of Viswanath had the bails off in a flash. The Pakistan captain walked back for 48. The score read 131 for seven.

Tahir Naqqash was the new batsman, and Sivaramakrishnan tossed up yet another inviting one. Naqqash slammed it high towards the deep. It was almost a hat-trick, but Amarnath at long on did not quite get into position in time. The ball cleared him and bounced inside the ground before going over the fence.

It was now Shastri’s turn to get a wicket. Naqqash drove hard at a wide one, and Viswanath’s wonderful anticipation and hands made the catch look incredibly easy.

In the next over, the mesmerising Sivaramakrishnan continued. The new man, Dalpat, took a swish at a leg-break and it was fielded at cover. The next ball was similarly tossed up, wide, only turning the other way. Dalpat repeated the stroke and Shastri made no mistake this time. It was 145 for nine.

With several overs to go, it looked likely that India would finish the tournament by bowling the opposition out in every outing. But, the last wicket pair held on. Wasim Raja, the eternal fighter, one of the best lower middle order scrappers produced by Pakistan, was playing in the tournament more as a leg-spinning all-rounder. No 8 was a bit too low for a batsman of his ability. But, he played the role to near perfection. At the other end, Azeem Hafeez survived 28 balls. Perhaps, the two left-handers found it easier to negotiate the spin attack with the balls turning into them. The innings ended at 176 for nine.

Srikkanth’s charge

It was a relaxed Indian team that had lunch. Yet, according to One Day Wonders by Gavaskar, it was Imran who had the biggest appetite. He tucked into the food with gusto unknown for men about to take the field. Gavaskar wrote that he saw Imran finish his huge meal with a flourish and approached him to express his surprise. Perhaps misunderstanding the Indian captain’s words, Imran responded by saying that he was sorry for what had happened. Probably a confession of the touch he had got to the keeper which would have made it 33 for five.

In any case, heavy meal or not, Imran started with a lot of fire. But, the situation as tailor-made for Shastri. He took all the time in the world, and the team could afford it. Playing himself in, eschewing every possible risk, he hung on at one end. At the other, Srikkanth was his characteristic self, essaying some breath-taking strokes with scant respect for grammatical correctness.

Hafeez was struck over cover for six, Naqqash flicked to square leg for four. A few overs later, Naqqash was hit in the air past mid-on for another boundary.

Wasim Raja’s leg-break was hoisted over long off. Cousin Rameez ran back, trying his desperate best to get to the ball. And as the ball landed in the crowd, the fielder ran into the fence and struck his chest against the pickets. He clutched his chest and fell to the ground, gasping for breath. The Pakistani players ran towards him, trying their best to revive their mate. The physio and a medic ran in, and thankfully the crowd saw the injured man hesitantly get back on his feet. He walked off the ground to some generous applause for his valiant attempt.

Almost immediately, Srikkanth played another lofted drive towards long off. Malik got under the ball and ended up parrying it. It went for four. Fortune was favouring the brave and the reckless. At the other end, Shastri was calm, composed, his sole intention to keep his wicket intact.

In the 24th over, Srikkanth turned Wasim’s to the leg-side for a brace to complete his fifty. He celebrated it with a cut and a sweep for boundaries. At the halfway stage, India were 91 for no loss. A banner in the stands declared, “Down Under, India is thunder.” It certainly rang more close to the facts than its ‘bus driver tram conductor’ counterpart.

Champagne in a trophy

It took a second spell from Imran to strike the first blow. The ball was short and fast, and Srikkanth’s square-cut went like lightning to point. Raja clutched at a blinder. By then however, Srikkanth had scored 67 and the score was 103 in the 29th over.

It took a second spell from Imran to strike the first blow. The ball was short and fast, and Srikkanth’s square-cut went like lightning to point. Raja clutched at a blinder. By then however, Srikkanth had scored 67 and the score was 103 in the 29th over.

Imran ran in again, with the final burst of his energy, and produced a peach of a leg cutter. New batsman Azharuddin played at it and got the edge. It streaked through the gloves of Dalpat to the boundary. Imran fumed.

Azharuddin made merry, lofting Malik over his head, and then playing a delightful wristy pull off Naqqash. By the time he inside edged a drive onto his stumps, he had made an attractive 25 from just 26 balls. Just 35 remained to be scored.

Now, it was all Bombay professionalism. Vengsarkar joined Shastri and the score was steadily pushed along without providing the hapless bowlers any whiff of a chance. Only after he had got to the most patient of half-centuries in the 42nd over did Shastri open up. He lofted Naqqash to the wide mid-on for a boundary. He later stepped out to Raja, misjudged the length and his snick went straight into Dalpat’s gloves and out again. But, by then less than ten remained to be scored.

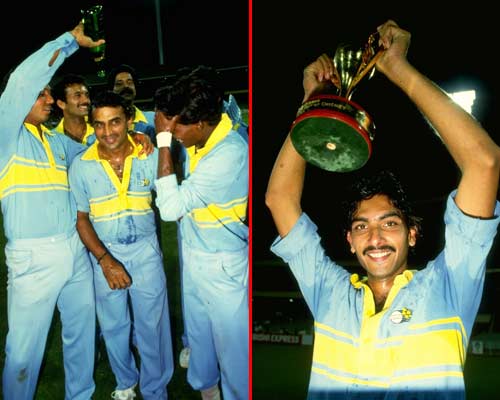

And finally Wasim Raja jogged in again, and Vengsarkar turned him past square-leg for the winning single. Eight wickets and 17 balls remained in the bank, as the victorious batsmen walked off with souvenirs and wide smiles.

Gavaskar, in his last match as captain of India, had the look of satisfied delight as he received the trophy. And it was soon put to excellent use. Shastri, presented with the Audi for his Man of the Series performance, did not have a driver’s license. Hence, the captain stepped up, and got in the driver’s seat. The team climbed in, some in front, some in the back, some on the roof and some on the boot. Mohinder Amarnath sat on the boot, pouring champagne into the trophy and drinking it down.

The celebrations continued at the Hilton Hotel with several of the local fans of the Indian team joining in.

For the Indians, the tournament had been a story of clinical efficiency. They had performed to perfection and had sailed through the matches virtually unchallenged.

The Indian players and public wanted this win for a very specific reason. It was underlined in a ‘Benson and Hedges World Championship Special’ crossword puzzle published in one of the major sports magazines of the country.

The clue to 17 across read: “Two world championships mean that the first one was not a —— (5).” Yes, the answer was ‘Fluke’. The Indians had heard it repeated too loudly, too unkindly and too often that the 1983 World Cup had been a lucky bolt in the blue. They wanted their team to silence the doubters for good. Their heroes could not have done a better job.

Brief scores:

Pakistan 176 for 9 in 50 overs (Javed Miandad 48, Imran Khan 33; Kapil Dev 3 for 23, Laxman Sivaramakrishnan 3 for 35) lost to India 177 for 2 in 47.1 overs (Ravi Shastri 63*, Krishnamachari Srikkanth 67; Imran Khan 1 for 28) by 8 wickets.